Related Resources

For Understanding Trauma

How Traumatic Stress Impacts the Brain

Did you know that your brain is designed to find the difficult moments in every day? Our little friend “Amy” the amygdala loves to search out those hard moments—those difficult experiences that lead to feelings of anxiety, frustration, and sadness.

Counterintuitively, the reason for this is she’s always trying to keep us safe. The unfortunate side effect is that when we have a difficult moment Amy will start spinning worst case scenario stories about these experiences. I like to think of it as a choose your own adventure of doom that our brain will take us on in order to keep us prepared for every eventuality. For anyone who’s ever experienced ruminating thoughts then you know how painful this can be.

Luckily there are easy steps we can take to stop ruminating in its tracks and instead let our amygdala know that we are safe and sound.

Understanding the Impact of Stress & Trauma: The Window of Tolerance

In this psychoeducation video, Dr. Kate Truitt walks us through the window of tolerance and the impact of long-term stress and trauma on the mind and body. She begins by explaining that experiencing a traumatic event can change the way our mind and our body show up in our day to day lives, and it can be for a short time after the trauma or can create long-term change. Our mind and body are a closed loop system, what impacts one impacts the other.

Dr. Kate then explains that the window of tolerance is the body in its optimal state, where it can access both reason and emotion. Outside of the window of tolerance is hyperarousal (over-reactivity, unclear thoughts, emotional distress, anxiety) and hypoarousal (depression, unmotivated, numbness, fogginess, fatigue). When we experience a traumatic event, it can push us out of the window of tolerance to hyperarousal or hypoarousal.

In a healthy mind body system, our system will rebalance. But if we experience a big enough stressor or prolonged stressors, we will start cycling between the red and the grey zone state. This can often look like a cycle between anxiety and depression. If we stay in this cycle, our window of tolerance shrinks.

Dr. Kate reminds us that we have the power of neuroplasticity in our hands!

Understanding Trauma (YouTube Playlist)

Dr. Kate Truitt begins by introducing this 37-episode series, where she covers the intricacies of trauma, such as post-traumatic stress injury and complex trauma. This includes addressing questions such as why do some people have PTSD and others don’t, how many adverse childhood experiences do we have and what trauma does to the brain and body.

In this series, we dig deep into how to go from being survivors to becoming thrivers, or learning how to “Phoenix up.” This means taking the experiences of our past and turning them into personal empowerment. The story of the phoenix illustrates a fire bird that flies into flames to burn up. It consistently rises stronger and wiser than ever before. The bird chooses to burn up, so that it can rise, and Dr. Kate explains that this is the opportunity with trauma.

Forfeiting the Self as a Trauma Response: People Pleasing & Fawning

By Dr. Kate Truitt

This is the third in a series of four blog articles about understanding and healing trauma.

For better or worse, your friend Amy, the amygdala, plays a pivotal role in how your brain helps you make sense of the world. She helps you create and design the world you live within, a big part of which is your relationships with others.

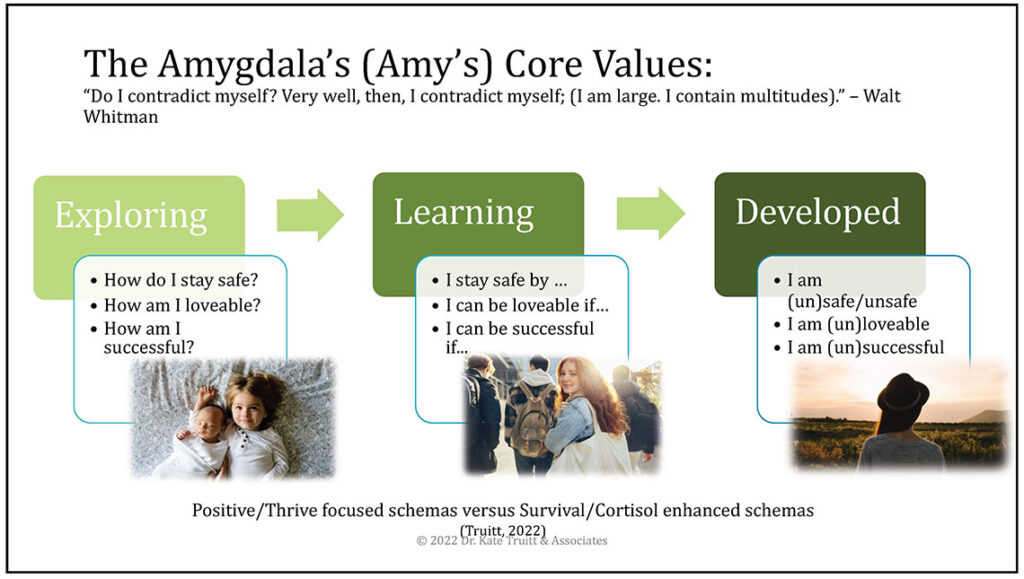

Considerations of Self: Amy's Core Values

Your amygdala is continuously on guard, looking out for us. In this pursuit your little friend has three basic considerations for you. Since infancy we have been developing your sense of the world and your place in it through the lens of what I call Amy’s three core values. These are:

How do I stay safe?

How am I lovable?

How am I successful?

As you develop through childhood and adolescence, your brain sorts through these three core values, saying:

I can stay safe by___________________.

I can be lovable if __________________.

I can be successful if________________.

The lessons you have learned to fill in those blanks have come from your caregivers, your peers and the world around you. They tell you how to respond in difficult times. In the previous article in this series I detailed the trauma survival responses of fight, flight, and freeze. In this article I want to take a little more time on my personal go-to of the four F’s when I was growing up—Fawn, also known as people-pleasing.

Fawn: The Fourth F of Trauma Survival Strategies

If you have grown up in a difficult environment you may have learned through your developmental years that putting your dukes up, or running away/disconnecting, or staying small and quiet, are not the best options for staying safe and being lovable or successful. No, you instead might have learned to look through the lens of Amy’s three core values in the following manner:

I can stay safe by telling people what they want to hear and doing everything they want me to do.

I can be lovable if everybody likes me.

I can be successful if I make other people happy and help them be successful.

This is that fourth “F” survival strategy called Fawn, which most people don’t know much about. Fawning can be a bit counterintuitive, yet it is a powerful opportunity for healing. You can see right away that filling in the blanks above in this way is not a good plan for developing a healthy sense of Self, because in essence, fawning is all about forfeiting the self.

Fawn: Appeasing the source of the threat

When you choose fawn as a survival strategy you are appeasing the source of a threat that Amy sees in order to avoid conflict, even if it comes at the expense of your own sense of self-worth. People who fawn find their How am I safe? How am I lovable, and How am I successful? by falling in line with the wishes, needs and demands of others. People-pleasing becomes the go-to solution for defusing conflict, earning approval, placating abusers, and finding a “comfortable” place in relationships that are often dysfunctional and one-sided.

If you are fawning, you are ensuring that you have value to another person. You are aligning with their beliefs, their desires, and their needs. You are assessing who they are and what they are, and finding ways that you can be of support to them. You might argue “What’s wrong with that?” or “I’m just being a nice person.”

That’s the counterintuitive part. What is described in the paragraph above could be seen as a one-time solution for helping someone you care about that is in truly in need, and in that case, you are being a nice person. Fawning is something different. It’s a strategy for life’s difficult situations and moments, and it is often heaped on people who are not truly in need and who have become accustomed to benefiting from this behavior.

When you use fawning as a strategy you usually devalue yourself, especially when the subject of your attention is someone who is hurting you. And as a child or adolescent engaged in these strategies, you rob yourself of the chance to develop a sense of self, because if you’re constantly in a fawning state for survival, your self doesn’t matter. Only the perpetrators’ needs matter. That is a painful way to grow up and exist in the world. And the perpetrator usually does not care about your wants or needs.

Fawning as a barrier to healthy conflict

One example of fawn might be back in high school doing the cool girl’s homework to stay in her good graces and remain her friend. But think about it. What is the cool girl doing while you are in your bedroom at night alone doing your homework and hers? She’s probably out with all of the other cool girls doing cool-girl things. And do you think she would have been your friend if you had not agreed to do her homework?

Another aspect of our lives where fawning may present its itself is in response to conflict. An important thing to remember, especially when it comes to setting boundaries, is that not all conflict is bad. You can’t set a boundary without wading into a bit of healthy conflict.

As I have said before in this blog, the word, “no” is one of the few, and most important, words in any language that forms a complete sentence, and there is a bunch of conflict bound up in that word. Consider the following scenario.

Since more than a month ago you (let’s call you Liz), and your husband Evan have been hanging out on Saturdays with a new couple you met—Elena and Marco—doing things like going to the beach, or hiking—always something in the outdoors. Evan has grown to be big buds with Marco, and they even do things together by themselves sometimes during the week.

With you and Elena, not so much. Since day one that first Saturday, Elena has constantly been making critical comments to you—only within your earshot—about what you wear, how your body looks, and the way you say things. Since the second Saturday you have been wanting to tell Evan that you no longer want to hang out with this couple, although you are fine with Evan hanging out with Marco, who is a nice guy. You even meekly suggested this after the second weekend, but Evan waved it off and said you were just being too sensitive.

Because you wanted to avoid conflict with Evan, as you often do, you acquiesced and kept up the new Saturday ritual. Now it is the Friday night before the fifth Saturday and Evan is excitedly talking about the day ahead. You are dreading it. This can’t go on. You gather up the strength to say that one-word sentence and you finally do:

“No.”

“Count me out!” you exclaim. “I am not going to spend another Saturday with that woman quietly slipping me comments like, ‘You could really benefit from getting a gym membership like I have,’ or ‘Gawd, where did you get that dress!’ or lifting her eyebrows at me when I decide to order an appetizer. I am not going. If you want to hang out with Marco in the future, that’s fine. He’s a nice guy. But if I have to go tomorrow I am going to loudly tell Elena off to her face, and it won’t be pretty. And that probably won’t be good for you and Marco going forward. I’ve had it!”

Evan is taken aback by your strong response, but he puts his arms around you and says, “I’m sorry, Liz. I didn’t realize it was so bad. I should have listened to you the first time.”

“No, I should have been more forceful and insisted the first time,” you say.

Obviously Liz learned the strategy of fawning to appease someone else long before she met Evan, because evidently he is not one who seeks to benefit from her tendency toward fawning.

This is an example of how fawning becomes forfeiting the self. Again, not all conflict is bad, and avoiding it can make things worse.

As a businessperson I have learned that avoiding conflict can be as harmful to an organization as it can be to a person or a relationship. As actor, writer and director Robert Townsend once said, “A good manager doesn’t try to eliminate conflict; he tries to keep it from wasting the energies of his people. If you’re the boss and your people fight you openly when they think that you are wrong—that’s healthy.”

Separating Need-To From Want-To

When you choose fawn you learn to set aside your value and to not set boundaries and instead to exist in a world of overextension and self-sacrifice. The opportunity in fawning is that you can begin to change the process quickly, simply by moving into identifying what your unique wants and needs are. I want to caution that if this is the first time you have tried this, it can be difficult. In fact, if you have grown up in world where fawning is a primary survival strategy, you may not even have a sense of who you are in the world around you. The following shift in perspective is the key to your opportunity to change.

When you are people pleasing and fawning, every behavior you engage in feels like a need to behavior, I need to do this to stay alive. But here is the trick. Need to behaviors are actually tied into your core biology: I need to breathe, I need to go to the bathroom, I need to eat food. Those are the real need to behaviors, which leaves a whole host of other things that you’re doing that are want to behaviors, such as, “I want to walk my dog because I want to make sure that she’s healthy and happy and also that she’s not doing her business in my house.” When you look at things this way, if you are in a fawning relationship, or more than one, you can start breaking apart the need to from the want to in these relationships, which can create the foundation for setting boundaries.

This process will take time. That organic pull from your past inclining you toward fawning can be strong because it has been with you for so long. You can take a step back and with loving self-compassion ask yourself: “Do I need to do this in order to survive?” or “Do I want to do this for this person?” and then even create a third unique category: “Maybe I don’t even want to do this.” Place that behavior into one of those categories, and start teaching your brain to create these micro separations so that you’re empowered to start moving into agency within these relationships.

If you start to realize from this article that you might be engaging in some fawning behaviors, start empowering yourself to make intentional change. Again, change is slow, and it can take time, but it will help you begin to learn about who you are, what you need to do, what you want to do, what might you do even though you don’t really want to do it because it’s important to you, and what you might just stop doing. It can help you figure out what is really not tied to your survival, so you can choose for yourself whether you have to do it anymore. This is an exciting place to be when you gets there.

For more information on fawning and setting boundaries in relationships, see our blog article titled, “Setting Boundaries: Bringing Ourselves Into The Equation of Our Relationships” and visit our YouTube Playlist “Understanding Trauma” in the sidebar to this article.

Trauma is diffuse, and it is not just about our thoughts and our emotions. It’s about the entire mind/body system. As I explored in our September 2022 blog article, Healing Trauma: The Mind and Body Remember, our emotional and physical health and well-being are undeniably entwined and intricately connected. Anything—not just trauma—that impacts our body will impact our mind and vice-versa.

The good news is that we have the power of self-healing in our hands with the mindful touch of The Havening Techniques. If you want to read more about this healing opportunity, continue from the September blog article above into our October 2022 blog article titled, The Havening Techniques: New Neuroscientific Insights Shine Light on Ancient Healing Practices.

If you are interested in building your own personalized self-healing journey, check out my book titled, “Healing in Your Hands: Self-Havening Practices to Harness Neuroplasticity, Heal Traumatic Stress, and Build Resilience,” released in December and available on Amazon.