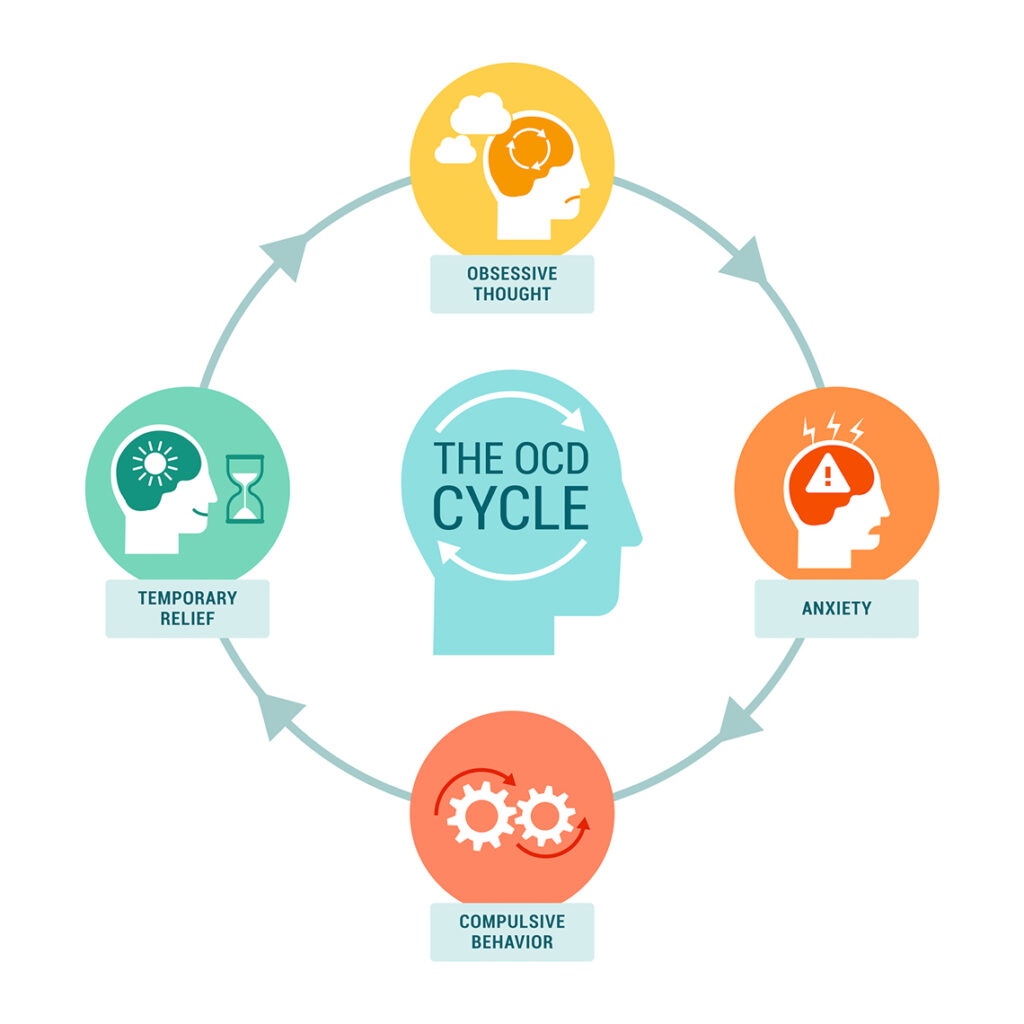

In this guided meditation, Dr. Kate will demonstrate the process of Creating Personal Resiliency to help soothe your anxious brain. You will learn how to practice CPR for the Amygdala®, which engages the self-havening touch, a practice mentioned in past videos. Dr. Kate will invite you to turn inward and notice/rank an experience of distress or disturbance that has continued to cause ruminating anxiety or worry from your Amygdala, or a physiological experience of tension or stress.

She will then walk you through visualizing a personal journey that activates all your senses and will use breathing exercises to further enhance relaxation. This calming video will take you to a safe space within your mind’s eye where you can appreciate the beauty of what your very own visualization can create.